Best Practices for Classroom Prompting for Special Needs Students

Types of Prompts and How to Use Them to Teach New Skills

| February 2016When teaching children with special needs new skills, therapists and teachers typically provide prompts to guide the process. According to activity-based curriculums, prompts are defined as supports, and may come in many different forms. Prompts are ever changing, depending on the activity.

A wide variety of prompts enables special education classroom staff to choose the one or combination that are most effective for each particular child. Examples of classroom prompts include:

- verbal prompts – instructions or words to direct the child to complete the skill. It is the most commonly used prompt.

- modeling – demonstrations of the skill either in person or by video. It is the second most commonly used prompt.

- manual prompts – physical contact from a teacher or therapist or support provided by adaptive equipment (or a combination of the two) to help the child complete the skill.

- gestural prompts – pointing, motioning or nodding toward the child or the objects to complete the skill.

- photographs and line drawings – pictures or step-by-step instructions to complete the skill.

- text prompts – written instructions, checklists, scripts and reminder lists.

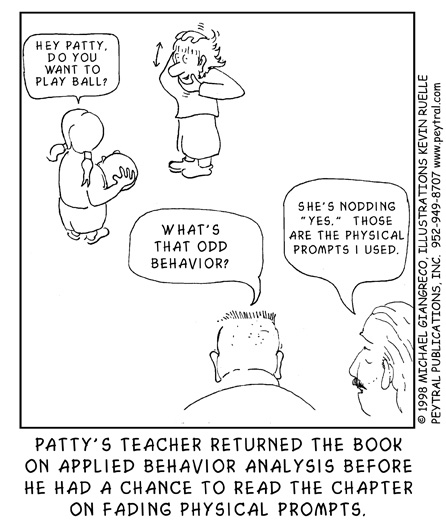

These prompts are certainly necessary during the skill acquisition phase, but in order for the special needs child to become fully independent in the skill the prompts eventually need to be phased out. This great cartoon demonstrates what happens when we fail to decrease prompts:

Image used with permission.

Eight Techniques for Effective Prompting

#1 Start with the least amount of prompts possible (“least to most method”). Begin with minimal assistance and only add additional prompts if needed. Prompt along a continuum of verbal prompt, gestural prompt, modeling and then a manual prompt. Sometimes even with one type of prompt you can move along a continuum of least to greatest prompts. For example, use one verbal request. If needed, add additional verbal requests. The benefit to this technique is that with every additional prompt needed the child is getting repeated time to respond to requests and more practice time. This “least to most” approach is a good choice for skill assessment to determine how much of the skill the child can do independently.

#2 Reduce the prompts as the child learns the skill (“most to least method”). When special needs children first learn a new skill they may need physical cues, modeling and verbal prompts. For example, a motor skill such as sitting or walking may require the support of adaptive equipment. As the child learns to master parts of the skill we gradually reduce prompts to encourage full independence by the child. Some research indicates that reducing prompts is the most effective fading prompts technique because it results in fewer errors and quicker skill acquisition than the “least to most method.”

#3 Delay prompting by increasing the amount of time before you offer the assistance. For example, when providing a verbal prompt wait three seconds before providing the manual prompt. When the child is ready, try to fade the prompt by providing the verbal prompt, then wait five seconds and if the child does not complete the request, only then provide the manual prompt.

#4 Grade the guidance you are providing for manual prompts. The instructor can gradually change the intensity or location of the manual prompt. For example, if the child initially requires support at the trunk to master upright postural control, over time you may be able to provide support more distally at the arm as the child’s core strength improves. As another example, for a fine motor task you may initially need to provide hand over hand manual guidance. Over time, slowly grade the guidance to just the wrist, then elbow, then shoulder, then standing behind and finally moving away entirely.

#5 Gradually fade the properties or characteristics of the materials used to elicit the skill. For example, during a classroom table activity, if you want the child to point to a specific object perhaps you make that object stand out more during early trials (i.e. “Point to the red circle” and the red circle is bright red versus the other choice which may be a dull green circle). Then as the child responds correctly decrease the difference between the two choices. As another example, perhaps during an ADL task, you offer the child motivational and fun tools to complete the skill but over time you gradually fade the use of the fun tools and replace them with everyday objects.

#6 Prevent prompt dependence. The child should respond to the prompts and relevant cues, not just the prompts. Fade prompts as quickly as possible to avoid prompt dependence. For example, when a child is first learning a new classroom skill, responding to prompts can be rewarded. As the child progresses, reward or affirm the child when unprompted responses occur. Some research indicates that rewarding more unprompted than prompted responses results in more correct responses and more rapid learning. Another example of the importance of fading prompts relates to the practice of functional motor skills. Whenever possible, reduce manual prompting to challenge the special needs child’s ability and encourage intense practice at a level that requires problem solving and enhances motor learning.

#7 Return to the previous levels of prompting if errors occur. When the child practices the skill the next time provide enough prompts to decrease the chance of errors again.

#8 Evaluate the effectiveness of prompts. Use direct observation and data collection to determine what prompts are successful and when to fade the prompts. For example, documenting the specific supports in use with adaptive equipment allows you to record the reduction of support over time. Try to do short term trial runs in the classroom of different types of prompting to create a plan of action. Remember to treat each child and each skill as a whole new set of circumstances and don’t necessarily rely on previous observation and data to determine new prompts for different skill sets.

The next time you are teaching a special needs child a new skill remember to have an ongoing evaluation of the prompts you are using, how are you using them and a plan to fade the prompts as quickly as possible. Educate all the people who interact with the child to make sure all of you are using the same classroom prompting techniques.

References:

MacDuff, Gregory S., Patricia J. Krantz, and Lynn E. McClannahan. “Prompts and prompt-fading strategies for people with autism.” Making a Difference: Behavioral Intervention for Autism (2001): 37-50.

Levac D, Wishart L, Missiuna C, Wright V. “The application of motor learning strategies within functionally based interventions for children with neuromotor conditions.” Pediatric Physical Therapy 2009; 21(4):345-355.

Aykut C. “Effectiveness and effi ciency of constant-time delay and most-to-least prompt procedures in teaching daily living skills to children with intellectual disabilities.” Educational Sciences: Theory and Practice. 2012; 12(1): 366-73.

Fentress, GM. “A comparison of two prompting procedures for teaching basic skills to children with autism.” Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2012; 6(3): 1083-90.

The original version of this article first appeared in Your Therapy Source.